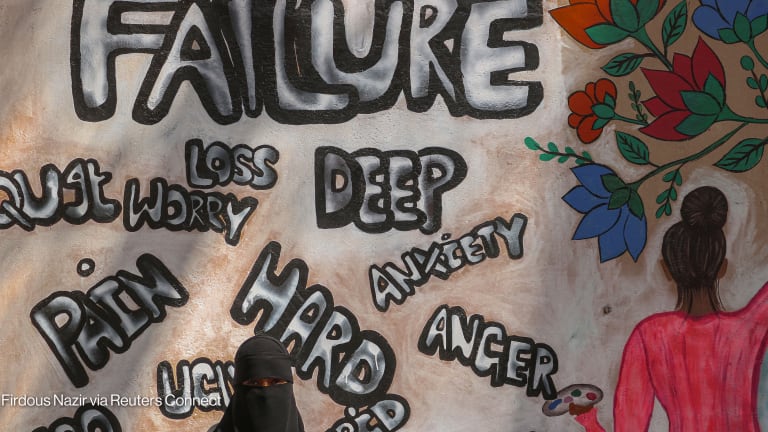

Aid workers on the front line in humanitarian crises are liable to suffer from a hidden and largely ignored problem — a mental health crisis.

Seventy-nine percent of global development professional respondents in a mental health and well-being survey reported experiencing mental health issues that have compromised the quality of their lives and relationships.

More on mental health

► The power of mindfulness in a war zone

Working on the frontline of humanitarian crises, these men and women may have witnessed human suffering first-hand. As a result, they are more likely to suffer from symptoms such as flashbacks, severe and often debilitating anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and nightmares. One of the most common disorders is post-traumatic stress disorder.

As a clinician working with aid workers and social entrepreneurs around the world, Dr. Paul Hokemeyer has seen how this suffering can become imprinted in the most primitive part of the aid workers brain, known as the limbic system. This can alter how the world is perceived, creating a hyper-awareness of threats and a high alert for danger. This hyperreactivity can lead to acting out in compulsive and self-destructive ways.

It’s not just symptoms of PTSD that aid workers have to deal with. Other factors that can impact their mental health include loneliness due to constant travel; increased safety concerns linked to facing organized crime, corruption, bribery, and active work in war zones; and economic stress due to underpayment.

While there are a number of effective clinical interventions for dealing with individual trauma responses, more needs to be done at an institutional level to bring about change.

Here are three things employers can do to help protect the well-being of their staff.

1. Work toward destigmatization

While it is positive to a see more public discussion around mental health — including by the U.K.’s Prince William and Prime Minister of New Zealand Jacinda Ardern during the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos, Switzerland, earlier this year — a culture of stigma still surrounds mental health.

NGOs and international development organizations need to lead by example and show their aid workers that it’s OK to be vulnerable and open up about their mental health challenges. The process of openly communicating and showing support for their mental health needs can start as early as in the employment background screening.

Similar to the startup world where investors take the “investor pledge” to make a public commitment to take an active role in mental health, NGOs, and international development organizations can do exactly the same. It can guide aid workers to the right organizations and present a public differentiator.

2. Provide training

Aid organizations have to provide better training and support for managers, who oftentimes are first-responders to the mental health needs of staff. They need to better understand strategies to spot staff with mental struggles, as well as be able to direct them to tools and other resources necessary to help their aid workers in the field.

3. Increase well-being resources

The international aid community requires a mindset change in which it expands its horizon beyond a core focus on addressing humanitarian needs by also taking into account the mental and physical well-being of its most important asset: frontline aid workers.

Just because an aid worker has committed to making a positive difference in the lives of those caught in conflict doesn’t mean that they are immune to the struggles, tragedies, and pain encountered in the process. Aid organizations have a responsibility to make sure their staff have access to a sophisticated network of mental health professionals.

A recent article in The Economist outlined an affordable and scalable approach, task-shifting, established by the World Health Organization to train numerous people in providing basic mental health support to the war victims in need in places such as Syria and Iraq.

Despite the ubiquitous resource constraints in the international development sector, the same approach can and should be applied at scale to help humanitarian and aid staff without creating a significant financial burden for organizations.

The world is suffering under the weight of economic inequality, environmental degradation, and geopolitical shifts. Aid workers work to serve those bearing the brunt of these forces. We must nurture them and support their work, which means investing in their mental health.

The resources exist to help them. It’s time to redouble our efforts to give them the support they need to continue with their work as healthier and more productive aid workers.