Opinion: The fight against TB, paused by COVID-19, must resume

The COVID-19 pandemic has devastated lives, economies, and health systems, across the world with record-breaking speed. In doing so, it has seemingly pushed aside tuberculosis, another deadly airborne infectious disease.

But TB didn’t go anywhere. People just got distracted, health workers were redirected, and health systems became overwhelmed. In just a few months, the pandemic reversed years of progress made in the fight against TB. Recovering from this setback is an urgent priority.

TB can be prevented, diagnosed, treated, and cured. Yet each year, 3 million people with TB around the world are unable to access diagnosis and life-saving treatment. In 2019, TB was responsible for 1.4 million deaths around the world; India accounted for 31% of it. Although globally, COVID-19 caused more deaths than TB in 2020, TB remains the foremost lethal infectious disease in most low- and middle-income countries.

More TB news:

► A new TB preventive therapy aims to increase patient compliance

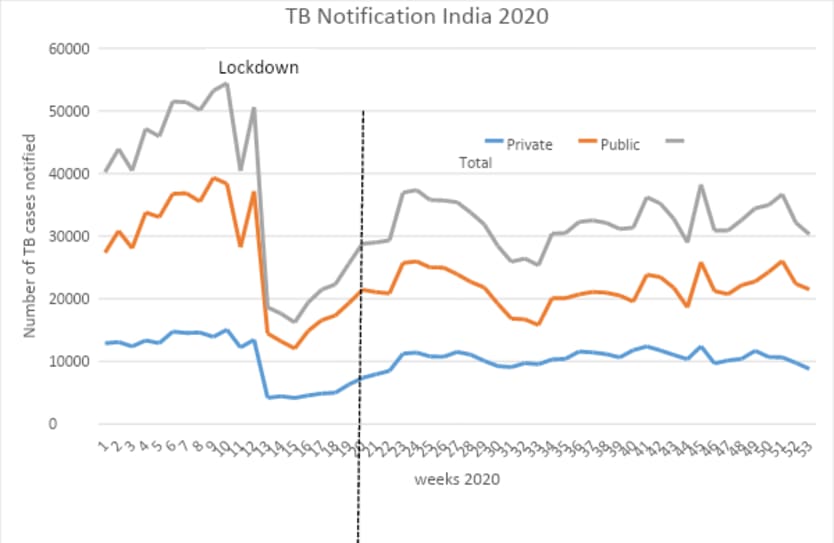

When the pandemic triggered lockdowns in March 2020, diagnosis and enrollment for TB treatment fell dramatically in many high TB-burden countries. A May 2020 modeling study showed that such a decrease could reverse hard-fought gains achieved in the last five to eight years.

India recognized this problem early, as TB notifications plummeted in its online real-time surveillance system “Nikshay,” during the lockdown period. India aims to end TB by 2025, five years ahead of the global Sustainable Development Goals target. COVID-19 threatened to derail this commitment. A high-level committee under the chairmanship of the Indian Minister of Health & Family Welfare developed a rapid response plan by August 2020.

The key components of India’s response plan include integrating TB and COVID-19 in all outreach, including screening programs, and laboratory services. Efforts to locate TB and COVID cases in all health care facilities intensified, and rapid molecular testing for TB expanded. Bi-directional screening of TB in COVID patients, and in patients displaying influenza-like illness and severe acute respiratory infections were implemented to augment surveillance.

Contact tracing systems and testing for TB linked to COVID contact tracing were quickly set up throughout the country. Private sector TB care facilities were reopened, and digital tools were rolled out to help patients stick to treatment regimens, among other measures.

By December 2020, India had almost closed the growing gap on TB treatment enrollment, with its figures for the month only 12% lower than before the pandemic. A quarter of the diagnosed cases were identified through active TB case-finding.

This recovery in India is ongoing. An early lesson is that recovery efforts succeed with political leadership and substantial resources, along with an insistence that COVID-19 outreach and prevention efforts include TB work, instead of replacing it.

Certainly, the programs that helped bring India’s TB efforts back up to speed can be replicated anywhere else in the world with sufficient resources and political will. Another key element in India’s response is the tracking system that rang the alarm in the first place.

The Stop TB Partnership and the U.S. Agency for International Development have preliminary data to suggest that nine high TB burden countries representing 60% of the global TB burden had a decline in TB enrollment in 2020 ranging from 16%-41%. A 20% global drop in TB treatment enrollment pushes the TB response to 2008 levels in terms of people diagnosed and treated. Twelve years of hard work and investments are simply lost, and we see ourselves on a difficult path to recovery. As India demonstrates, this recovery is possible. It requires speed, focus, commitment, and funding.

We call on ministers of health from countries with the biggest recent decline in TB diagnosis and treatment to join India and urgently — within the next six weeks — develop and execute operational recovery plans. Engagement of local leaders, as well as community and civil society organizations in full partnership with public and private sector partners is essential. Development partners and donors, especially The Global Fund, will need to fully support these plans and efforts.

World leaders must also continue to focus on TB. As G-20 countries together account for 50% of the global TB burden, the G-20 agenda for 2022 and 2023 must target TB. With India and Indonesia, the top two high TB burden countries, both about to assume G-20 presidencies, we have an opportunity that we cannot let slip away.

We also ask that the U.N. General Assembly have a special UN High-Level Meeting on TB in 2023. We call upon the secretary general’s office, all partners of the Stop TB Partnership and the World Health Organization to pursue this.

COVID-19 devastated our TB response, threatening years of progress in safeguarding lives around the world. We can change course; it is both in our power and a necessity.

Let us make sure 2021 is the year in which TB response rebounds stronger and charges forward.

Search for articles

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5