When reading an academic article about global health, you may focus on how a study was conducted, what the major conclusions are, and how it advances the field of study. What you may not realize is that the research you are reading is likely skewed.

A major academic paper recently demonstrated what scientists across Africa have been concerned about for a while: They do not get to talk about research conducted on their continent. The reasons are related to resources and logistics. For many scientific endeavors, primary funding is mostly provided by Western agencies — usually to a Western primary investigator who then engages an African partner. Since these institutions possess resources to generate data and conduct data analyses — and have more experience in publishing scientific findings — this pattern feeds the notion that Western agencies and their employees can own the data.

Fortunately, there is renewed discussion on why global health organizations must address the colonial roots of international health and how global power dynamics continue to play an important role in who gets to talk about their research.

Creating tangible opportunities in a move toward equity

What needs to happen now is that global health organizations need to follow through on these abstract discussions and create tangible opportunities with scientists from Africa to shift toward equity. This will require increased engagement and investment toward building research capacity in Africa and establishing equitable coalitions at every layer of global health care delivery. To a certain extent, these initiatives have started to emerge: For instance, the London-based charitable organization Wellcome Trust has shown interest in shifting the “center of gravity” of biomedical research to Africa’s leadership. While commendable, these minor changes will not be enough to address upcoming challenges in global research leadership.

In recent years, artificial intelligence, blockchain, and other evolving technologies have been playing an increasingly important role in the delivery and improvement of health care services — often characterized as the Fourth industrial revolution. These emerging technologies provide a promising solution to solving chronic developmental challenges in low- and middle-income countries, especially in Africa.

Nevertheless, these technologies either remain poorly accessible or have only thrived in select African countries such as South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, and Kenya. Notably, even in countries where technology is flourishing, the risks associated with the rapid changes are real, and most countries remain largely unprepared for potential pitfalls.

Disrupting existing models

One area that has rapidly evolved in recent years is big data and its ability to disrupt existing service models in most economic and social sectors, including delivery of banking, health care, and educational services. These evolving technologies present an unprecedented potential to disrupt many other service categories. There has been an increase in the number of global health funding agencies calling for open data access approaches such as Plan S — an initiative for open-access science publishing that was launched by Science Europe in September 2018. This plan requires researchers who benefit from public or state funds to publish their work in open repositories by 2021.

Currently, most major funding agencies agree that research data should be made publicly available in a timely manner. However, promotion of open-access and open-source policies on a continent such as Africa — a place that has been vulnerable to exploitation through normalized “helicopter research” — may prove to be counterproductive and might limit the strengthening of an already weak African research and development ecosystem, exacerbating the profound disparities in affordability and accessibility of health care services already observed globally. This is a problem.

Historically, even in partnerships perceived as “equitable”, most data are analyzed and published in the West and little benefit accrues for the African scientists and communities involved in the research. This has led to heightened mistrust among developers and scientists in Africa and their counterparts in the West.

How to change this trend

Recently, the magazine The Scientist published a worrying report on how the U.K.-based Sanger Institute was planning to commercialize a genetic array that was developed using DNA samples from Africa, potentially violating the terms of agreement that governed the use of these samples. These reports have sparked a new conversation on the ethics around biospecimen and data sharing, particularly in this era of increased genomics research in Africa.

There is a sense of urgency and frustration, as many African countries do not have the appropriate enforcement policies in place if biospecimens or data are removed from the continent. Some arrangements have involved a mandatory moratorium to allow African scientists to clean, mine, and publish their research data before it becomes publicly available.

One of the examples is the Human Heredity and Health in Africa, or H3Africa, consortium, which has set clear policies on data sharing. For instance, H3Africa scientists are accorded a minimum of 11 months before genomic data can be openly released, and the data is under an additional 12 months of publication embargo thereafter, allowing a total duration of 23 months before data is available for secondary research. H3Africa also includes specific guidelines on biospecimen collection, transfer of data, and biorepositories.

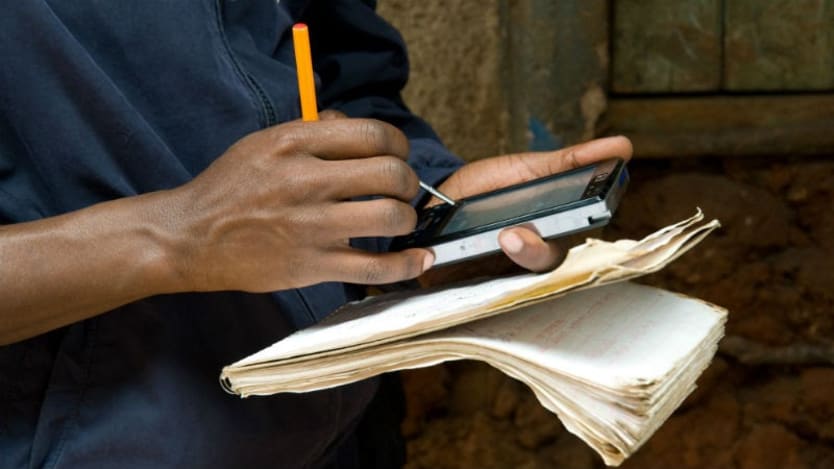

Even with these restrictions, the moratorium does not efficiently consider relevant limitations in the African context: limited computer literacy and opportunities for developing skills in data science, insufficient cloud-computing capabilities to handle big data, low or nonexistent digitized health research data, and poor internet bandwidth.

Here is what we need to do to change this trend:

First, governments in African countries should be proactive in adopting new technologies. Institutions of higher learning should also adapt quickly. They should design and develop novel courses that can train the next generation of students to produce a skilled mass of individuals who can meet the imminent need.

Secondly, regional institutions working closely with their international technical partners need to adopt “smart” technologies such as blockchain in designing agreements that promote the trackability of data and biospecimen for benefit-sharing. Developing these facilities will ensure African institutions and scientists are able to participate equitably and enable an open research platform that can benefit broader communities in the region.

Thirdly, privileged Western institutions need to be intentional in making these technologies accessible and affordable in different African countries. This would enable increased uptake and implementation of novel research techniques. To achieve this, high-resource Western partners can participate in training and developing local expertise as well as providing funding to set up the required high-level computing systems in these countries to establish technical collaboration. They can take inspiration from various working groups and committees being formed by collaborative agencies such as H3Africa.

None of these ideas are easy, but they are necessary if global health organizations are serious about developing equitable health care delivery systems in Africa. It is time to challenge the entrenched power dynamics. While we should continue to think globally about how to address the biggest challenges in international health, health funders and research leaders need to work toward creating, developing, and — more importantly — sponsoring local voices.