South Sudan's future depends on getting children back in school, aid actors say

AWEIL, South Sudan — South Sudan has the highest proportion of out-of-school children in the world, with more than 2 million children who aren’t receiving an education as of 2018, up from 1.7 million in 2013, when the country erupted into fighting, according to the United Nations.

“A whole generation of learners are out of school, jeopardizing their futures and the future of the country,” said Nor Shirin Md Mokhtar, UNICEF South Sudan’s chief of education.

In March, UNICEF, together with the World Food Programme, launched an education in emergency project aimed at providing daily meals to 75,000 children at schools across the country while also training 1,600 teachers and helping improve facilities in at least 150 schools.

“If we had formidable education, one that instills positive attitudes, desirable values, skills, and knowledge, then there would be no way thousands of young people would be mobilized to destroy their own country.”

— Valentino Achak Deng, teacher and founder, VAD FoundationThe two-year, $24.4 million program, funded by the European Union, is the first joint initiative of its kind in South Sudan.

It’s a welcome step in helping hungry children concentrate and stay in school, but thousands are still unable to step foot in a classroom due to a number of other barriers to education present in the country.

While the nation’s crippling five-year civil war has played a role in the disparity, donors and aid groups are concerned that ongoing factors including access to schools, lack of trained teachers, poverty, and challenges in changing cultural perceptions about the importance of education could also impede progress.

‘I have no money to go to school’

Crouched in the dirt in a tent in South Sudan’s northern town of Aweil while the U.N. launched its new education program across the yard, 11-year-old Awer Agorong hangs his head. “I’m hungry and I have no money to go to school,” he said, fiddling with a button on his shirt.

On South Sudan:

► Under a shaky peace deal, is it too soon to invest in South Sudan's development?

► South Sudan aid sector 'infected' with bribery, local NGOs say

► Aid workers warn against repeating South Sudan peace deal mistakes

Even though public schools across the country are supposed to be free of cost to attend, according to the ministry of education, many still charge fees for uniforms, books, and other resources, making it hard for poor families — who don’t always know they’re entitled to free education — to send their kids to class.

Children who do go to school are often packed into overcrowded, dilapidated classrooms.

At the Sacred Heart of Jesus primary school in Aweil, for example, 44 teachers serve 2,450 students — a 55-to-1 student-teacher ratio — said Gnor Garang, the school’s headmaster. The ideal teacher to student ratio is 40-to-1, according to a staff member at UNICEF South Sudan.

Some children in remote areas of the country don’t have access to classrooms at all, learning under trees and forced to stay home when it rains. The conflict has also partially destroyed between 20%-44% of schools across the country, according to the U.N. During a visit to Central Equatoria state in February, Devex drove by a school still occupied by government soldiers.

As South Sudan slowly emerges from years of war with a fragile peace deal signed in September, the government has vowed to make education a priority. Part of South Sudan’s 2040 goals is to “build an informed nation,” said Deng Deng Hoc Yai, the minister of education.

“But we can’t do that unless everyone goes to school,” he said.

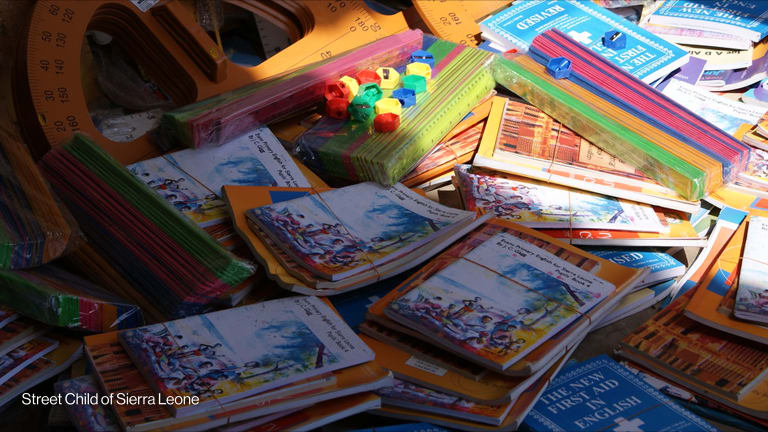

The government has pledged to increase spending on education from 10.5% of the national budget to 15% for the next financial year. Together with UNICEF, it has helped develop a new curriculum and textbooks, and it hopes to train more than 40,000 teachers on how to use and teach the materials in the next three years, Yai said.

Currently, however, much of the education sector is reliant on external partners, including aid groups and private donors.

Over the last decade, Valentino Achak Deng, who has his own harrowing story of survival as a small child during Sudan’s second civil war, opened two model schools in the former state of Northern Bahr el Ghazal through his VAD Foundation, a nonprofit focused on education. Deng, a teacher himself, attributes a lot of the nation’s problems to a lack of learning.

“It’s the very reason we are where we are,” Deng told Devex. “If we had formidable education, one that instills positive attitudes, desirable values, skills, and knowledge then there would be no way thousands of young people would be mobilized to destroy their own country,” he said.

In 2009, Deng started a boarding school in his hometown of Marial Bai and in 2018 he opened an all-girls primary and secondary school in Aweil, both fully funded by private donors including support from actor George Clooney and human rights activist John Prendergast.

Five hundred women and girls attend the school in Aweil, which is free of charge and costs approximately $200,000 a year to operate, Deng said. The budget for the boarding school in Marial Bai is roughly double that, he said.

Getting teachers and students in the classroom

One of the biggest challenges Deng faces is finding quality teachers. Teaching is not a well-paid job, and many trained educators leave South Sudan for different countries or change professions for better paying opportunities with aid organizations because they can’t afford to feed their families, he said.

In an attempt to keep teachers in the classroom, the European Union has funded a consortium including consulting firms Charlie Goldsmith Associates and Mott MacDonald to implement a program that pays 30,000 teachers across the country $40 a month on top of the approximate $10 a month they receive from the government, said Imke van der Honing, country coordinator for CGA. The program, which began in 2017, monitors teachers’ attendance and pays them based on whether they show up to class.

Additionally, between 2013-2018, the U.K. Department for International Development funded a project to support girls enrolled in school with cash transfers of the equivalent of approximately £18 ($22.8) a year as well as schools with cash grants.

UNICEF doesn’t have figures for the total number of girls out of school, but between 63%-89% of 5-year-old girls are estimated to be out of school in the country, according to a joint U.N. report. With the help of the U.K.-funded program, enrolment for girls almost doubled during the four years it was operational, van der Honing said. The cash support for students gives their families agency to make their own decisions rather than relying on humanitarian aid, he said. Phase two, funded by DFID, began in May.

Combatting cultural perceptions about the importance of education is another challenge, especially in pastoralist areas where high importance is placed on cattle and where families often use children to tend to the cows rather than send them to school.

Pastoralist families that decide to educate their children sometimes send the ones who aren’t deemed as smart, said Gamal Batwel, deputy country coordinator for CGA. “[They] keep the clever ones for the cows,” he said. He remembers building schools in Eastern Equatoria state between 2006-2008, which ended up being used for animals to sleep in. The situation is slowly changing now and some of those schools are being used for learning, he said.

In an effort to impart the importance of education to remote communities, one nationwide education program, Girls’ Education South Sudan, comprised of locals and internationals and funded by UK Aid, produced radio programs highlighting the value of education and brought the radio shows to the communities, said Akuja de Garang, the group’s team leader.

But for things to steadily improve, “much more attention” has to be given to the quality of education, said CGA’s van der Honing. He’s urging organizations focused on education in South Sudan to increase engagement and coordination with the government and for donors to focus more on systems and sustainability.

On education:

► Global education community clashes over GPE private sector strategy specifics

► In Morocco, can education stem undocumented migration?

► PISA founder Andreas Schleicher on the future of the education ranking

The European Union, which is investing €67 million ($74.66 million) in the education sector between 2016-2020, acknowledges that the competition for resources in South Sudan is “huge,” said Massimo Stella, program manager for education with the EU in South Sudan. Investing in education is vital for sustained peace and will take a coordinated effort within the sector as well as a long-term approach, he said.

Deng, who runs the two schools in Northern Bahr el Ghazal, wants donors and the government to change strategy in terms of education. Instead of providing blanket support for thousands of schools, he suggests creating specialized, model schools to give students who do well in exams access to higher quality learning.

The country can’t keep relying on aid groups to shoulder the burden, he said.

“Look at the NGOs, they have limits, they can’t be in the country forever,” he said. “We should not take the education of our children for granted. It would be a huge mistake and would affect the country for many years to come.”

Search for articles

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5