Where is Kamala Harris on US foreign aid?

For nearly four years, Kamala Harris has been in U.S. President Joe Biden’s shadow — but that doesn’t mean she’s a blank slate.

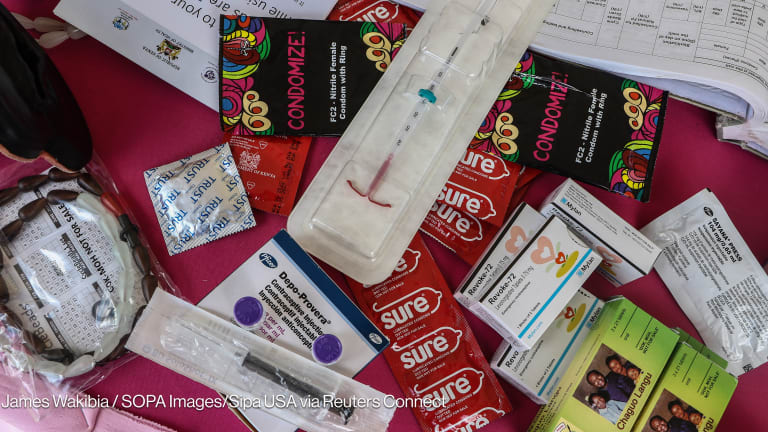

At just past 10:30 Thursday night, the Democratic National Convention erupted into applause. Kamala Harris, the current vice president of the United States and Democratic Party nominee for president, was walking toward the stage — and as she made it to the podium, Harris laughed as she tried to calm the crowd. “Let’s get to business,” she said, as cheers spilled from the convention hall. “Let’s get to business.” For weeks, that’s exactly what many had been waiting for. Ever since President Joe Biden stepped down from the race, questions have been swirling about what a Harris presidency could mean for U.S. foreign affairs — and on the last night of the Democratic National Convention, the nominee finally began to provide some answers. The vice president spoke of continuing her efforts on immigration, maintaining strong support for Ukraine, and defending Israel’s right to protect itself. At the same time, Harris emphasized the suffering across Gaza and stated she and Biden were working to ensure Palestinians would soon see “dignity, security, freedom, and self-determination.” Still, after nearly four years in Biden’s shadow, it’s difficult to untangle how Harris’ approach to foreign affairs might differ from her former running mate’s, especially when it comes to the role of foreign assistance across the world. “I don’t think there will be many differences between the two in terms of their overall approach,” said Tod Preston, the executive director of the Modernizing Foreign Assistance Network, an advocacy organization focused on U.S. foreign aid. “They have very similar world views, and very strong beliefs in the importance of global engagement and multilateral partnerships.” Even so, Harris’ role within the Biden administration — and her track record as a U.S. senator — may provide clues to how a Harris presidency could shape the development world. Following the party line Earlier this week, the Democratic Party released its 2024 platform: a 92-page vision of what a new Democratic president would focus on over the next four years. Though largely centered on domestic policy, the platform highlights the current administration’s work on several international issues, from combating climate change to alleviating global food insecurity and supporting women’s reproductive health. “We must rally the world to address the challenges that impact all of us, from climate change and global health to human rights, technology, food security, and inclusive economic growth,” the platform reads. The document — which was finalized just days before Biden dropped out of the race — centers on Biden. With just 32 mentions of Harris compared to 287 mentions of Biden, the platform details how the current president would have taken things forward in his second term. Despite that, the Democratic National Committee endorsed the platform on Monday night, further cementing the link between Harris and her predecessor. “It makes a strong statement about the historic work that President Biden and Vice President Harris have accomplished hand-in-hand, and offers a vision for a progressive agenda that we can build on as a nation and as a Party as we head into the next four years,” the Democratic National Committee wrote upon releasing the platform Sunday evening. Though such platforms aren’t binding, they do set out a blueprint of what a party hopes to accomplish if their candidate makes it to the White House, explained Marjorie Hershey, a professor of political science at Indiana University. It also reflects the fact that right now, many feel Harris’ approach to foreign affairs will be more of a difference in tone than in substance, she explained. Two weeks after clinching the candidacy, Harris has still not published any policies on her website, foreign affairs-related or otherwise. “While we know the broader vision of the Democratic Party, it’s a bit unclear what Harris would want to prioritize and where she would want to make her mark,” said David Cronin, a government affairs specialist at Catholic Relief Services. “I think she understands that foreign aid is both a moral good and a strategic tool, but she hasn’t had a lot of opportunities to be out in front of these issues.” Still, Cronin said, that’s not to say Harris has been completely on the sidelines. She’s traveled across the African continent to follow through on Biden’s commitments to reengage; she’s been in lockstep with the president on the U.S. support for Ukraine. Harris has also highlighted Israel’s right to defend itself against Hamas, though often placing a more forceful emphasis on the suffering of Palestinians than Biden. And, she led the administration’s push to address the root causes of Central American migration to the U.S., a strategy that included parsing out millions of dollars in humanitarian relief. “We can’t forget she has been on the global stage as a vice president for the last four years, and she has been a U.S. senator,” Cronin said. “She may not be as seasoned as Biden was, but these issues aren’t entirely new to her either.” ‘All in on Africa’ Last March, Harris stood beneath the Black Star Gate — the entrance to Accra’s Independence Square — in Ghana’s capital. It was the first leg of a weeklong journey across Africa, one that sought to deepen relations between the U.S., Ghana, Tanzania, and Zambia. “As President Joe Biden said at the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit last December, we’re all in on Africa,” Harris told the thousands of young people gathered before her. “We are all in, because the fates of the American people, and of America and the continent of Africa, are interconnected and interdependent.” Harris’ trip was one of many attempts to reframe the relationship between Africa and the U.S. While the Trump administration’s Africa policy centered on trade, investment, and U.S. competition with China, the Biden administration attempted a different tack. They emphasized the importance of African leadership in solving the world’s crises and organized the second-ever U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit to bring delegations to Washington. “Our relationship with Africa cannot and should not and will not be defined by competition with China. The vice president’s trip will illustrate that we have an affirmative agenda in Africa,” said senior administration officials before Harris’ trip last year. “We want to expand African options, not limit them.” While on the continent, Harris met with the leaders of all three nations, along with young people, female entrepreneurs, business leaders, and philanthropists. She also announced a series of multibillion-dollar commitments from both the U.S. and the private sector, with $1 billion focused on closing the digital gender divide, and another $7 billion centered on climate adaptation, resilience, and mitigation across Africa. “My visit has convinced me more than ever that we must all, around the globe, appreciate and understand the importance of investing in African ingenuity and creativity,” Harris told leaders in the private and philanthropic sectors, according to remarks published from the last day of her trip. “I am convinced we’ll continue to unlock the incredible economic growth and opportunities that we have seen thus far to the benefit of the entire world.” Africa has shown up in Harris’ portfolio in other ways. As a senator, she co-sponsored legislation requesting that the U.S. Agency for International Development create a plan to address the needs of girls affected by extremism and conflict, which was created to recognize the 4th anniversary of the girls kidnapped by Boko Haram in Nigeria. As vice president, she announced the creation of the President’s Advisory Council on African Diaspora Engagement, which sought to enhance dialogue between the U.S. and African communities. During her trip to Africa, she visited the Zambia home of her grandfather, drawing a personal connection between her upbringing and the continent. Over the last three-and-a-half years, the Biden-Harris administration also committed nearly $20 billion to health programs across Africa, while also delivering over $13 billion in emergency aid and food security assistance across the continent, according to the Democratic Party platform. “Throughout her vice presidency, [Harris] has been really involved in Africa,” one former senior administration official told Devex. “She has a great record, and I'm very hopeful and fairly confident that she's going to continue to build on it.” Even so, Harris’ smooth reception in Africa isn’t a sure bet. Though her Africa trip was largely praised as a success when she landed in Ghana, the country was discussing a bill that could imprison its LGBTQ+ citizens — and in a speech in the West African country, she called for “all people to be treated equally.” Her remarks followed years of support for the LGBTQ+ community during Harris’ years in the U.S. Senate, where she co-sponsored multiple related bills, including one that would establish a permanent special envoy at the State Department for LGBTQ+ rights. Harris’ speech was later blasted by the country’s speaker of Parliament, Alban Bagbin, who urged Ghana’s lawmakers not to be “intimidated by any person.” One year later, the country passed a bill that would impose a prison sentence of up to three years for anyone convicted of identifying as LGBTQ+. “This is a broad generalization, but the ruling class — and the political elite in Africa — probably secretly prefer Trump,” said one former diplomat who had served on the African continent. “A woman president coming to talk to [leaders in Africa] about democracy, or LGBTQ issues, or other things they don’t want to talk about may be a stretch.” Reproductive rights In 2022, Americans lost their constitutional right to an abortion. As states across the country began imposing policies restricting the procedure, Harris emerged as the administration’s front-runner on the issue — and earlier this year, she became the first vice president or president to visit an abortion clinic. “These attacks against an individual’s right to make decisions about their own body are outrageous and, in many instances, just plain old immoral,” said Harris, speaking at a Planned Parenthood in the country’s midwest. As a result, it’s no surprise that women’s reproductive rights have become a cornerstone of the Harris campaign. Earlier this week, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz, Harris’ vice presidential nominee, spoke about cementing abortion access across his state; last night, Harris spoke about how when Congress restores a bill to restore reproductive freedoms, as the country’s newest president, she would “proudly sign it into law.” Though the vice president’s focus on women’s health has been centered on the U.S., as a senator, she co-sponsored several bills that expanded reproductive rights issues to the international stage. That included a bill to permanently repeal the Mexico City policy, or the global gag rule, a piece of legislation that bans U.S. funding for foreign organizations that provide abortion services with non-U.S. dollars. Though the bill Harris co-sponsored was stalled and later reintroduced in the Senate, for many, Harris’ engagement on such issues is a hopeful sign. “This is the first time that we have the potential for a president to be unapologetically and outspoken in their support for abortion, and this could translate — for the first time — to foreign policy as well,” said Beth Schlachter, the senior director of U.S. engagement at MSI Reproductive Choices, a nonprofit organization that provides reproductive health care. But while it’s one thing to advocate for reproductive rights domestically, it’s quite another to do so abroad. For six decades, the Helms Amendment has prohibited the use of foreign assistance to fund abortion services. Though the amendment makes exceptions in cases of rape, incest, or risk of life to the mother, for years, there has been confusion around what those exceptions mean programmatically, often leading to an overimplementation of the policy by USAID partners. On top of that, the flip-flopping of the Mexico City policy — along with changes to reproductive rights within the U.S. — has complicated other countries’ understanding of what the world’s largest reproductive health donor does or does not allow. “Let’s assume she wins,” said the former diplomat, who now heads an organization focused on global health. “The policy language will be better, and we will be excited and enthusiastic about it. But the bureaucracy will continue to be really conservative about these issues on the international front.” “Unless there’s a concerted effort from a Harris White House to really push this language, the bureaucracy is just institutionally cowardly on this issue, and will not lean forward unless it's really prodded to do so,” the diplomat added. Though one part of Schlachter agrees, another part of her feels that Harris — with her decades of commitment to reproductive rights, and her connection to the issue as a woman — could be the one to make that change. “If this isn’t an opening, for the love of God, what’s it going to take?” Schlachter asked. Immigration On her first international trip as vice president, Harris spoke from a podium in Guatemala City. She was there to discuss migration from Central America to the U.S. and had a message for anyone thinking about doing so. “Do not come,” Harris said, shaking her head. “Do not come.” Her remarks were criticized by some progressives in her party and leveled against Harris by those across the aisle. Many on the right began calling the vice president the “border czar,” and blaming Harris for the thousands coming across the border. But Harris’ mandate was much narrower than that, explained Doris Meissner, the former commissioner of the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service. While the Department of Homeland Security continued to manage migration, Harris was charged with the more diplomatic mission of tackling migration’s root causes. Even so, the criticism seemed to stick. “Almost right out of the box, things started to go badly,” said Meissner, who is now a director at the Migration Policy Institute. “But even though that was all the case, the way she did deal with the root causes strategy was pretty sophisticated.” Part of the root causes strategy included immediate assistance. Even before her trip to Guatemala, Harris announced $310 million to address what the White House called the “acute factors of migration” in Central America, such as hurricanes, the COVID-19 pandemic, and climate change. Harris also launched task forces around anti-corruption and anti-migrant smuggling, encouraging the United Nations to develop a regional Humanitarian Response Plan to drive more money toward the region. And, just like in Africa, Harris focused on building public-private partnerships and generating private-sector investment. Two years after her visit to Guatemala, Harris had announced more than $5.2 billion in commitments across the three countries, with more than 50 companies and organizations agreeing to support “inclusive economic growth” in the region, according to a White House press statement. Those companies included Meta, which agreed to train thousands on digital financial services; and Corporacion AG, Central America’s largest steel producer, which planned to create more than 500 full-time jobs, according to the White House. Still, a Harris presidency won’t just mean money for the region, Meissner explained. On Thursday night, Harris said she would bring back a bipartisan immigration bill that was introduced earlier this year — one that unraveled after Trump called it a “very bad” piece of legislation, and soon after, all but four Republicans failed to move it to the Senate floor. Her actions may also resemble those of Biden, who signed an executive order blocking migrants from receiving asylum when border crossings ticked up in June. Though the move drew fierce criticism from immigrant rights groups, illegal border entries reached a three-year low. “On immigration, I think that you're going to see the prosecutor side of her, the rule of law side of her,” Meissner said. “The idea that we have to confront this, and it can't just continue to go on the way it has gone on in the past.” Global leadership Harris, like Biden, has also sought to split herself from the global isolationism that so defined former U.S. President Donald Trump. On the second day of her vice presidency, Harris spoke with the director general of the World Health Organization, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, about her administration’s reversal of Trump’s decision to withdraw from WHO, according to a White House press release from that day. Soon after, Harris spoke at the 65th session of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women, where she stated that the U.S. was strengthening its engagement with the U.N. and other multilateral institutions. “The status of women is the status of democracy,” Harris told the commission. “For our part, the United States will work to improve both.” On Thursday night, Harris continued that trend, emphasizing her commitment to “stand strong” with America’s NATO allies and reiterating previous comments around global leadership — especially when it came to confronting whom she referred to as “autocrats” — that she had made on the vice presidential trail. “America, let us show each other and the world who we are, and what we stand for,” Harris said. Devex Senior Reporter Adva Saldinger contributed to this story. Update, Aug. 23, 2024: This article has been updated to clarify that the Helms Amendment does not prohibit U.S. funds from being used for abortion in the cases of rape, incest, and to save the life of the woman, though implementation of those exceptions can cause confusion.

At just past 10:30 Thursday night, the Democratic National Convention erupted into applause. Kamala Harris, the current vice president of the United States and Democratic Party nominee for president, was walking toward the stage — and as she made it to the podium, Harris laughed as she tried to calm the crowd.

“Let’s get to business,” she said, as cheers spilled from the convention hall. “Let’s get to business.”

For weeks, that’s exactly what many had been waiting for. Ever since President Joe Biden stepped down from the race, questions have been swirling about what a Harris presidency could mean for U.S. foreign affairs — and on the last night of the Democratic National Convention, the nominee finally began to provide some answers.

This story is forDevex Promembers

Unlock this story now with a 15-day free trial of Devex Pro.

With a Devex Pro subscription you'll get access to deeper analysis and exclusive insights from our reporters and analysts.

Start my free trialRequest a group subscription Printing articles to share with others is a breach of our terms and conditions and copyright policy. Please use the sharing options on the left side of the article. Devex Pro members may share up to 10 articles per month using the Pro share tool ( ).

Elissa Miolene reports on USAID and the U.S. government at Devex. She previously covered education at The San Jose Mercury News, and has written for outlets like The Wall Street Journal, San Francisco Chronicle, Washingtonian magazine, among others. Before shifting to journalism, Elissa led communications for humanitarian agencies in the United States, East Africa, and South Asia.