ALICANTE, Spain — Of the top 20 climate funding recipients for water programs between 2000 and 2018, 19 were middle-income countries, according to new research by the Overseas Development Institute. Yet many of the world’s lower-income countries, particularly small island developing states, are considered the most vulnerable to climate change.

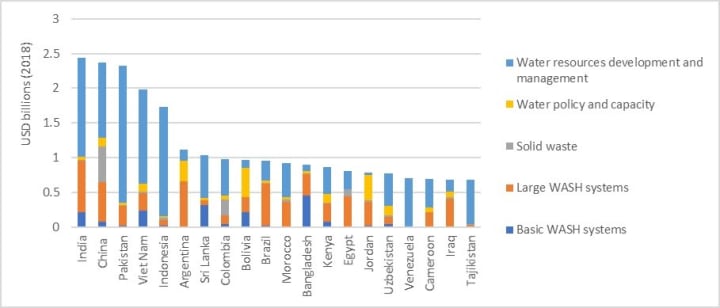

According to the report — commissioned by WaterAid to help establish where donors and national governments should reprioritize climate investment — India, China, and Pakistan received the most climate-related development finance for water programs at over $2 billion each in 2018. Researchers have called for a shift in focus to prioritize the most vulnerable.

“This report shows us that the world is not responding to the climate crisis by prioritizing the most vulnerable. Instead, the poorest communities, those on the front lines of climate change who are already feeling the impacts, are being left to pick up the bill themselves,” Jonathan Farr, senior policy analyst for climate change at WaterAid, said.

Bangladesh was the only lower-income country among the top 20 recipients. Last year, the country experienced extreme flooding, cyclones, and drought. Only two countries in sub-Saharan Africa — Kenya and Cameroon — were included in the top 20.

Explaining why investment into adaptation for water is needed — just 1% of climate investment goes to protecting and providing such services for vulnerable communities, according to the report — Farr said extreme weather events can directly affect the quality and availability of water sources and sanitation systems, which can impact people’s health and prosperity. For example, a small flood in an area with poor sanitation could lead to a cholera outbreak, which could interrupt education and earning potential.

While many middle-income countries face these challenges and require investment to safeguard water, sanitation, and hygiene, Farr said that they have the capacity to identify the problems as climate-related and raise money, something lower-income countries might lack.

This could be one reason why donors are directing money to middle-income rather than lower-income countries. “If you try to get climate finance you need to make a case for it … if that data’s not available then it’s very hard to do that,” Farr said, adding that the people who are least able to adapt are also those least able to ask for help.

“This research should be a wake-up call to refocus on helping the people and countries that are most vulnerable to climate change and related threats.”

— Nathaniel Mason, research associate specializing in water, sanitation, and climate change, ODIWhile there isn’t an explicit objection to funding low-income countries’ climate-related water programs, Saleemul Huq, director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development in Bangladesh, said it’s more of a failure to prioritize it.

“History shows us promises are made and are hardly ever kept, so we are relying on ourselves to fill the gap and do what we can. We welcome the support but it’s not a begging bowl, we’re not waiting for that to happen,” he said.

Nathaniel Mason, research associate specializing in water, sanitation, and climate change at ODI, said researchers had looked at whether the top recipients’ prioritization of water within their nationally determined contributions had any relationship to their receipt of climate finance for water but found little relationship.

“This research should be a wake-up call to refocus on helping the people and countries that are most vulnerable to climate change and related threats, to listen to their priorities better, and to think more creatively about how we finance climate change adaptation,” he said.

As it stands, 86% of the finance offered to the top 20 countries for climate adaptation within the water sector came in the form of loans rather than grants. This means that governments from already heavily indebted nations have to choose between leaving their communities vulnerable to the impacts of climate change or getting into even deeper national debt.

“We have to keep pushing for more public international climate finance for climate adaptation, including for water, especially in grant form, to the poorest countries even while we acknowledge that the overall envelope is going to be constrained,” Mason said, referencing COVID-19.

But for Farr, it must go beyond asking for more money. He said the WASH sector must work together to help build capacity on the ground to assess, monitor, and manage climate threats.

“Even if there was lots of money if you don’t know what the problem is then how do you know what to spend the money on?

“We must meet this injustice with urgent and significant action on a global scale, and provide everyone, everywhere with the tools they need to combat the growing threat of climate change,” he said.

Visit the Turning the Tide series for more coverage on climate change, resilience building, and innovative solutions in small island developing states. You can join the conversation using the hashtag #TurningtheTide.