Some of the countries most vulnerable to climate change are the world’s 39 small island developing states, or SIDS. Home to approximately 65 million people, SIDS face many challenges, including rising sea levels, changing rainfall patterns, and storm surges, as well as deteriorating ecosystems.

Annually, the world loses approximately $63 billion because of stresses related to climate change, with a world average annual loss of less than 0.5% of global gross domestic product. In SIDS, however, this figure is much higher, reaching around 6.5% of GDP in Vanuatu and just over 4% in Tonga. Several island nations already experience strained economic systems; nine SIDS — including Haiti, Solomon Islands, and Timor-Leste — are categorized as least developed countries, or LDCs, yet also have to manage a high average annual loss due to climate change.

Multilateral channels are well-positioned to address the growing need of climate change programs in SIDS, with prominent initiatives such as Pilot Program for Climate Resilience and Least Developed Countries Fund. Another actor that has rapidly earned its position as one of the top climate-related support donors is the Green Climate Fund, which currently records more than $5 billion in approved funding across 37 SIDS.

While the potential of such funding flows is promising, larger economies are also beginning to recognize their role in climate-induced challenges faced by SIDS. New Zealand, for instance, has recently announced that two-thirds of its total climate-related support budget will be allocated to SIDS in the Pacific between 2019 and 2022.

As SIDS will be increasingly reliant on timely action and available funds from their neighbors, what does the current bilateral funding situation look like?

Devex has dived into data on environment and climate funding — the so-called Rio markers — to answer this question. The data, taken from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, encompasses approximately $4.4 billion across more than 5,500 projects in SIDS between 2013 and 2017. Here is what we found.

EU institutions leading the SIDS climate funding race

While Japan reported the highest funding with nearly $10 billion toward the Rio markers for all countries in 2017, it is European Union institutions that are leading the way in climate funding toward SIDS specifically.

In 2017, a total of $197.5 million, 94% of which was administered by the European Development Fund, was allocated across 11 countries. The largest EU funding has been received by Haiti with $109.1 million, Cuba with $24.5 million, and Jamaica with $18.7 million. These three are also the top recipient countries in the North and Central America region.

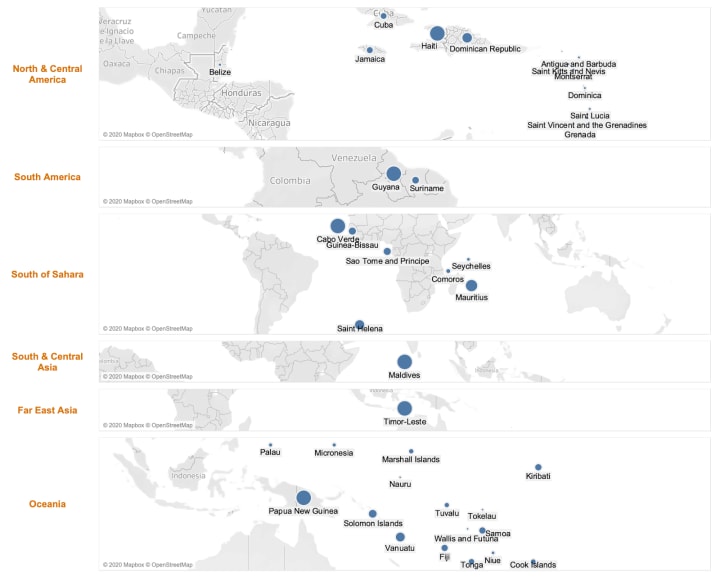

The North and Central America region is the one receiving the most funds, with a total of $444.3 million, which constitutes more than half of the total funds for 2017 at $866 million. The second-largest recipient, with a total of $348.5 million, is Oceania, followed by Far East Asia with $31.7 million, South of Sahara with $29.7 million, and South America with $11.6 million.

The region with least funding is South and Central Asia with $300,000, but this is largely because the Maldives is the only country in that region. At 16, Oceania has the highest number of nations.

Haiti is not only the top recipient in the North and Central America region, but across all SIDS, with $289.7 million allocated in 2017. The country has been funded consistently throughout the time period analyzed, receiving a total of around $840 million, with most of this addressing urban development; its biggest component is the EU’s URBAYITI program on building urban population resilience. Beyond the EU, the largest funder to Haiti is Canada, which, of a total $117.7 million provided in climate funding, allocated $113.4 million to Haiti in 2017.

Australia is the largest donor to Oceania, giving a total of $165.1 million in 2017, with the biggest share going to Papua New Guinea at $86.8 million. Its giving is allocated across 15 countries in Oceania — all of the region’s nations except for Wallis and Futuna — including four LDCs: the Solomon Islands with $22.4 million, Vanuatu with $19.4 million, Kiribati with $4.5 million, and Tuvalu with $1.2 million. Wallis and Futuna has received funding of $600,000 from France, which is the sole donor to the country — as is the case for Montserrat and St. Helena, where the U.K. is the sole donor.

Ownership is increasingly local

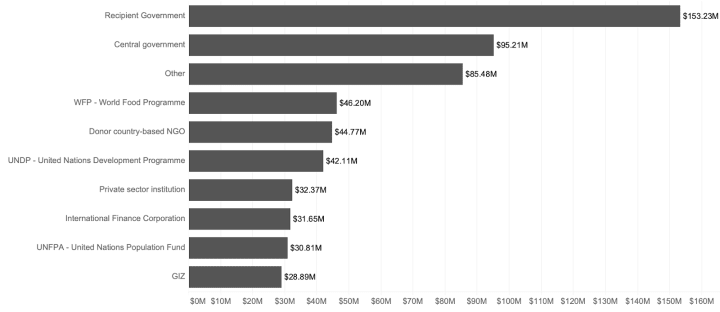

As the international development community is moving toward transferring ownership of program implementation and funding to local actors, shifts in the list of top recipients are becoming the norm. The case of climate funding to SIDS is reflecting this new reality: In 2017, more than $250 million was allocated directly to recipient country governments — including separate ministries that are not visible in the top 10 recipient organizations graph — particularly from EU institutions, Japan, and South Korea.

A substantial portion — approximately $150 million — of total funding for 2017 went through United Nations agencies such as the World Food Programme, United Nations Development Programme, and United Nations Population Fund. Although climate is often a crosscutting theme, the United Nations Environment Programme — whose primary mandate is related to the environment — received around $6 million, all from Norway.

Beyond the example of donors funding recipient government agencies directly, there is another example of an inherent split in the types of recipient organizations funded by certain donors. Most of Canada’s funding is targeting institutions, such as WFP, UNFPA, and the World Bank — with the last two having received funding solely through Canada. Funding from the U.S. on the other hand, is channeled through large U.S.-based contractors such as DAI and Chemonics International, respectively positioned 14th and 16th on the list of top recipient organizations. Around half of Australia’s funding in 2017 is simply tagged “other” — not naming a specific recipient organization — with the vast majority allocated to Papua New Guinea.

Climate change mitigation ahead of adaptation

The data analyzed and its Rio markers distinguish between five distinct categories — the so-called markers of environment: climate change mitigation, climate change adaptation, biodiversity, desertification, and a generic environment marker. These are also assigned to the projects according to their relevance; some projects are significantly connected, implying some connection, or principally connected, implying ultimate relevance, to certain markers.

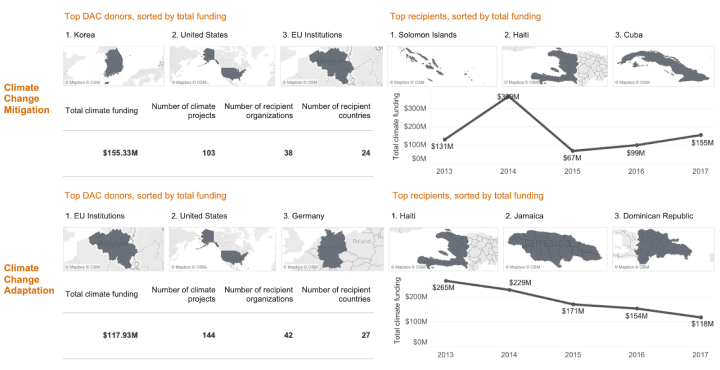

Climate funding reflecting differences between climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation markers. All graphs, except for the historical trends, are for 2017. It is worth remembering that around $30 million is tagged as both relevant to climate change mitigation as well as adaptation; separate numbers should not be added together, as they merely reflect the share of projects and funding relevant to specific markers.

Since SIDS only account for around 1% of the total carbon dioxide emissions worldwide, climate change mitigation initiatives — which involve projects aimed at reducing emissions and investing in green energy — would seem an unlikely intervention. However, around $155 million dedicated to SIDS across 103 projects in 2017 was tagged as being principally related to climate change mitigation — approximately $37 million more than for adaptation. Despite a drop in funding toward mitigation from 2014 to 2015, it is gradually increasing, especially in countries such as the Solomon Islands, Haiti, and Cuba.

South Korea was the biggest funder for mitigation in 2017, with the targeted sectors heavily focused on energy — such as hydroelectric power plants or energy policy. The biggest project in mitigation, worth $31.6 million, was funded by South Korea through the Export-Import Bank of Korea for the construction and operation of a hydropower generation plant on the Tina River in the Solomon Islands.

Another big project implemented by UNDP, with the support of $20.3 million from the EU, supports Cuba in its efforts toward an efficient and sustainable management of its resources.

Climate change adaptation, on the other hand, concerns itself with managing risks to health and livelihoods for people affected by negative climate change impacts. In the sphere of adaptation, EU institutions and the U.S. are spearheading the funding, with the highest amounts reaching Haiti, Jamaica, and the Dominican Republic. The historical flow has been steadily decreasing in the past few years, but adaptation efforts seem to have a wider reach with more projects across more countries. The main sectors underpinning climate change adaptation efforts include forestry services, material relief assistance, and agricultural development.

Whereas most funding for mitigation was channeled through the recipient government and a few multilateral actors, such as UNDP or World Bank Group’s International Finance Corporation, adaptation involved more private sector partners and donor country-based NGOs.

The two largest projects in adaptation are both funded by EU institutions: an $18.7 million investment in Jamaica for improved forest management, implemented locally by the recipient country government; and an $18 million response to Hurricane Matthew in Haiti, with a European NGO as the recipient organization.

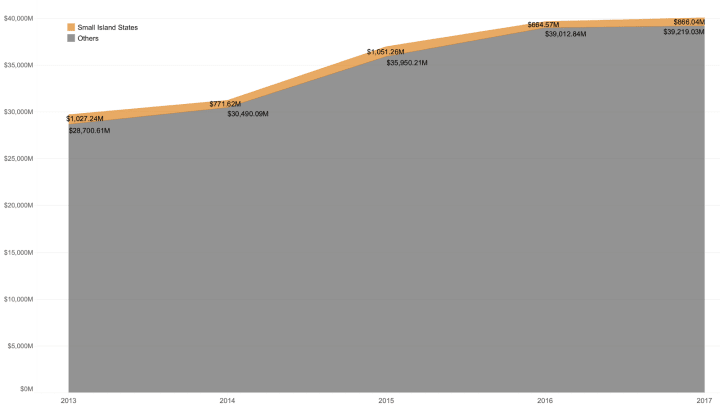

Although the volume of climate funding has in general increased over the past few years, rising from just below $30 billion in 2013 to approximately $40 billion in 2017, the share of the total funds going to SIDS is relatively modest. In 2017, climate-related funding to SIDS constituted around 2.2% of the total funds.

As SIDS continue to experience the impacts of climate change, it will be increasingly important to allocate sufficient funding to address the needs of some of these most vulnerable states.

Visit the Turning the Tide series for more coverage on climate change, resilience building, and innovative solutions in small island developing states. You can join the conversation using the hashtag #TurningtheTide.

More reading:

For more information on methodology and OECD classifications, please read the full Devex analysis of climate funding in the past five years.